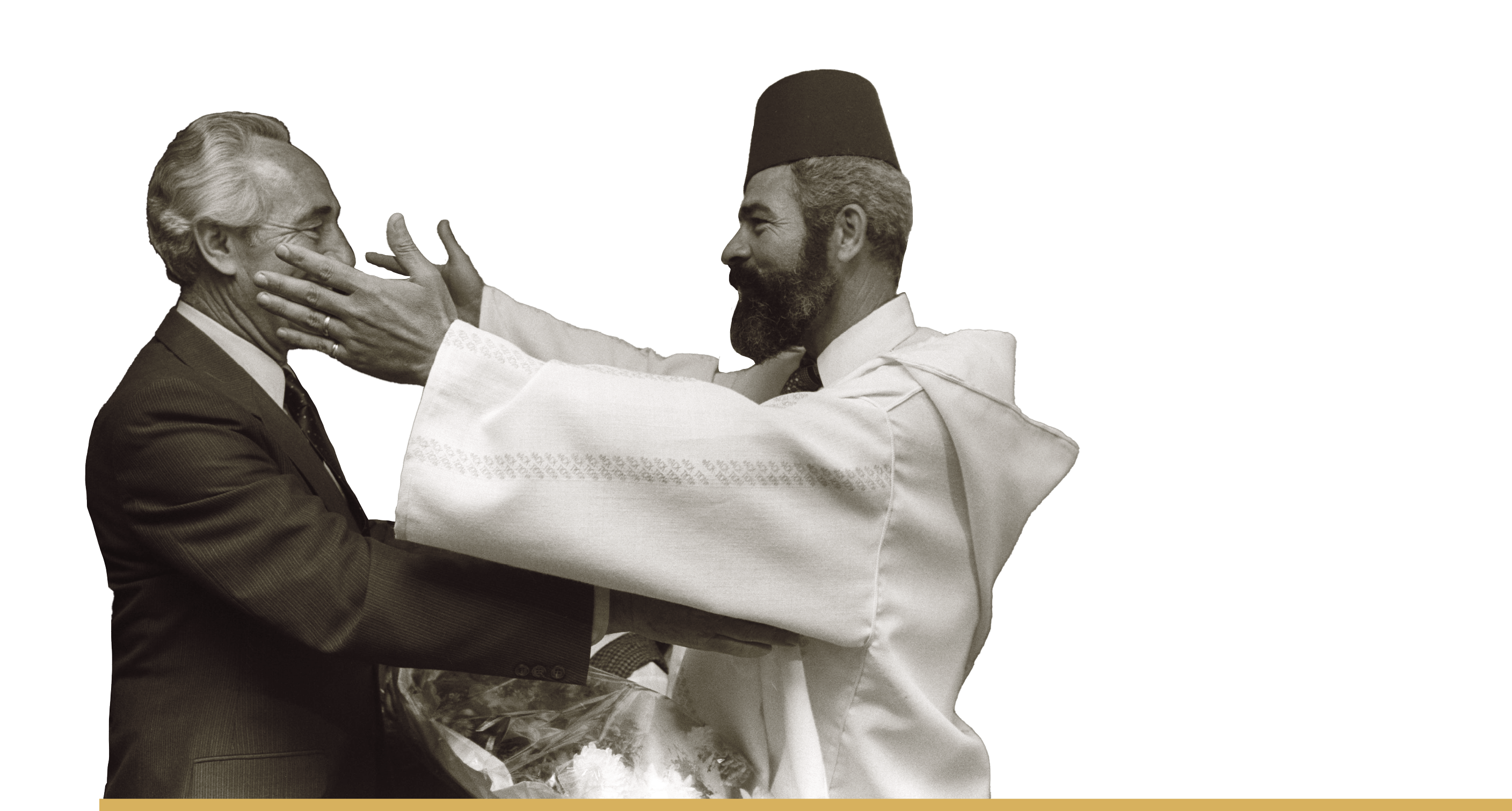

(GPO (Office Press Government | NATI HARNIK by I

About

Mimouna

Image by HARNIK NATI | Government Press Office (GPO)

A Brief History of

Jews in Morocco

Morocco has been home to a significant Jewish population for over two thousand years.

The Jewish presence in North Africa dates back to the migration following the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, in the year 587 B.C.E. The next period of Jewish migration to the Maghreb area (North Africa) occurred after the fall of Jerusalem in the year 70 C.E.

In the archeological site of Volubilis, a once-thriving Roman city in northern Morocco, archeologists found a tombstone with Hebrew inscriptions dating back to the 2nd century CE.

Read More >

The history of Judaism in North Africa is long and rich.

The Jewish presence in the Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya) dates back to the migration following the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, in the year 587 B.C.E. The next period of Jewish migration to the Maghreb occurred after the fall of Jerusalem in the year 70 C.E.

In the archeological site of Volubilis, a once-thriving Roman city in northern Morocco, archeologists found a tombstone with Hebrew inscriptions that date to the 2nd century CE.

The early Jewish inhabitants of Morocco are known as the Toshavim, the natives. This is the same word that has been used to refer to the Amazigh population in Morocco (colloquially known as the Berbers), as both communities arrived in the Magreb before the spread of Islam and Arabic. Next, in 1391 and later in 1492, when Jews were expelled by the Christian rulers of the Iberian Peninsula, many fled to Morocco, boosting the numbers of the already established communities throughout the country. The expelled Jews, or the Megorashim, built their own synagogues and continued their Sephardic mode of life in Morocco. The Sephardic traditions have largely influenced Moroccan Judiasm as it exists today.

Between the 9th and 20th century C.E., Jews in Morocco were subject to a status called Dhimma. It refers to the Pact of Omar treaty (9th Century) in which Jews and Christians, as the “People of the Book” living under a Muslim ruler, were given protection in return for paying a tax, al-Jizya in Arabic. Under some Sultans, the Jizya was intentionally set too high in order to force some Jews, espcially the poorest, to convert to Islam. This status was banished in the early years of the 20th century when Morocco became a French protectorate.

With the establishment of the modern state of Israel, the vast majority of Jewish communities in Morocco opted to migrate. This departure was motivated by both increasing anti-Semitic sentiment and the historic longing for Zion, the idea that the Jewish diaspora from around the world could be brought back to the biblical Land of Israel. This drastically changed Jewish life in Morocco, after more than two-millennia.

In response to increasing persecution and prejudice towards Jews in Morocco, other communities migrated elsewhere. The French-speaking Jews largely favored France and Canada; while many Spanish-speakers migrated to Venezuela, Argentina, and Brazil. However, the vast majority of Moroccan Jewish migration in the twentieth century was to Israel.

In their new countries, Jews from Morocco continued the traditions and customs that were best known to them. This included their local minhagim (Hebrew for “customs” or “traditions”), among which was the celebration of Mimouna.

Morocco has been home to a significant Jewish population for over two thousand years.

The Jewish presence in North Africa dates back to the migration following the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, in the year 587 B.C.E. The next period of Jewish migration to the Maghreb area (North Africa) occurred after the fall of Jerusalem in the year 70 C.E.

The history of Judaism in North Africa is long and rich.

The Jewish presence in the Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya) dates back to the migration following the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, in the year 587 B.C.E. The next period of Jewish migration to the Maghreb occurred after the fall of Jerusalem in the year 70 C.E.

In the archeological site of Volubilis, a once-thriving Roman city in northern Morocco, archeologists found a tombstone with Hebrew inscriptions that date to the 2nd century CE.

The early Jewish inhabitants of Morocco are known as the Toshavim, the natives. This is the same word that has been used to refer to the Amazigh population in Morocco (colloquially known as the Berbers), as both communities arrived in the Magreb before the spread of Islam and Arabic. Next, in 1391 and later in 1492, when Jews were expelled by the Christian rulers of the Iberian Peninsula, many fled to Morocco, boosting the numbers of the already established communities throughout the country. The expelled Jews, or the Megorashim, built their own synagogues and continued their Sephardic mode of life in Morocco. The Sephardic traditions have largely influenced Moroccan Judiasm as it exists today.

Between the 9th and 20th century C.E., Jews in Morocco were subject to a status called Dhimma. It refers to the Pact of Omar treaty (9th Century) in which Jews and Christians, as the “People of the Book” living under a Muslim ruler, were given protection in return for paying a tax, al-Jizya in Arabic. Under some Sultans, the Jizya was intentionally set too high in order to force some Jews, espcially the poorest, to convert to Islam. This status was banished in the early years of the 20th century when Morocco became a French protectorate.

With the establishment of the modern state of Israel, the vast majority of Jewish communities in Morocco opted to migrate. This departure was motivated by both increasing anti-Semitic sentiment and the historic longing for Zion, the idea that the Jewish diaspora from around the world could be brought back to the biblical Land of Israel. This drastically changed Jewish life in Morocco, after more than two-millennia.

In response to increasing persecution and prejudice towards Jews in Morocco, other communities migrated elsewhere. The French-speaking Jews largely favored France and Canada; while many Spanish-speakers migrated to Venezuela, Argentina, and Brazil. However, the vast majority of Moroccan Jewish migration in the twentieth century was to Israel.

In their new countries, Jews from Morocco continued the traditions and customs that were best known to them. This included their local minhagim (Hebrew for “customs” or “traditions”), among which was the celebration of Mimouna.

What Is

Mimouna?

The

tombstone a found archeologists, Morocco northern in Meknes of city the neighbors that city Roman thrivingonce a, Volubilis of site archeological the In. Jerusalem in Temple Second the of CE century 2nd the to date that inscriptions Hebrew with

are), Berbers the as known globally (population Amazigh the like just, Morocco of inhabitants Jewish early The

Iberian the from Jews expelled the of arrival the, 1492 in later and 1391 In. natives the, Toshavim the as known

expelled The. country the throughout communities established already the of numbers the boosted Peninsula

Morocco in life of mode Sephardic their continued and synagogues own their built, Megorashim the or, Jews

today Judaism M

Read More >

Mimouna is rooted in the tradition of conviviality and sharing; today, it has become a symbol of coexistence and living together.

Mimouna is a North African celebration that marks the end of Pesach (Jewish Passover) bringing to closure the prohibition of eating or owning Chametz (leavened foods). Customarily in Morocco, Jewish families would “sell” the Chametz to their Muslim neighbors who would then return it usually in the form of fresh cakes and cookies on the last day of the holiday. Following the massive departures of Jews from Morocco in the mid-twentieth century, the celebration of Mimouna transcended the borders and continued to be a yearly gathering of Moroccan Jews and Muslims.

The origin of the word “Mimouna” has various interpretations. Some believe the term comes from the Arabic word mimoun which signifies “chance” or “luck”. Others link it to the Hebrew word for faith, emunah, in order to give it a distinctively Jewish connection. Some scholars and rabbis also view the name as a connection to the commemoration of the death of Moshe Ben Maimon (the Sephardic rabbi Maimonides, who lived in the 12th and 13th centuries C.E.).

After the widescale departure of Jewish communities from Morocco in the mid-twentieth century, the celebration of Mimouna has once again transcended borders, where and continues to be a yearly gathering of the Moroccan diaspora of all religions and ethnicities.

Mimouna's

Symbolism

Mimouna is a joyous spring holiday that gathers friends and family, Jews and non-Jews alike, around a festive table filled with sweet delicacies and symbolic food.

In the post-Passover Mimouna celebration, it is tradition to open the doors of the home for guests to come in and join the festivities. The holiday emphasizes generosity and welcome, celebrating a culture of living together.

The common greeting for this holiday is said in the Moroccan Arabic dialect: trebḥu utse’adu. This translates to “May you be blessed with success and happiness.”

The

tombstone a found archeologists, Morocco northern in Meknes of city the neighbors that city Roman thrivingonce a, Volubilis of site archeological the In. Jerusalem in Temple Second the of CE century 2nd the to date that inscriptions Hebrew with

are), Berbers the as known globally (population Amazigh the like just, Morocco of inhabitants Jewish early The

Iberian the from Jews expelled the of arrival the, 1492 in later and 1391 In. natives the, Toshavim the as known

expelled The. country the throughout communities established already the of numbers the boosted Peninsula

Morocco in life of mode Sephardic their continued and synagogues own their built, Megorashim the or, Jews

today Judaism M

Mimouna is a joyous spring holiday that gathers friends and family around a festive table filled with sweet delicacies and symbolic food. On the Mimouna table you find: a live fish in a bowl which symbolizes fertility and abundance, stuffed dates, zaban (white nougat), candid eggplant, mrouzia (a sweet and spicey meat dish), milk, eggs, wheat, fava beans, and flour

(All recipes can be found in the “Build Your Event” section).

The celebration of Mimouna starts with the Havdalah ceremony “LeMotzei Yom Tov”, which officially ends Pesach, and the prohibition on eating chametz, foods from grain make with leaven.

When guests start arriving to the celebration, hosts often bless each guest using symbolic objects. These symbols differ by community. For example, some sprinkle a few drops of milk on the guests’ heads using lettuce leaves, while others sprinkle flour on guests with their hands. Some offer a date filled with almond-paste. When guest are greeted, the blessing spoken is always the same:

כִּ֤י אֹ֣רֶךְ יָ֭מִים וּשְׁנ֣וֹת חַיִּ֑ים וְ֝שָׁל֗וֹם יוֹסִ֥יפוּ לָֽךְ

חֶ֥סֶד וֶאֱמֶ֗ת אַֽל־יַ֫עַזְבֻ֥ךָ קָשְׁרֵ֥ם עַל־גַּרְגְּרוֹתֶ֑יךָ כָּ֝תְבֵ֗ם עַל־ל֥וּחַ לִבֶּֽךָ

[Phonetic Hebrew Reading]

Ki orech yamim ushenot ḥayyim veshalom yosifu lach. Ḥesed ve-emet al-ya’azvucha kashrem ‘al-gargeroteicha katvem ‘alluaḥ libecha

فَإِنَّهَا تَزِيدُكَ طُولَ أَيَّامٍ، وَسِنِي حَيَاةٍ وَسَلاَمَةً.

لاَ تَدَعِ الرَّحْمَةَ وَالْحَقَّ يَتْرُكَانِكَ. تَقَلَّدْهُمَا عَلَى عُنُقِكَ. اُكْتُبْهُمَا عَلَى لَوْحِ قَلْبِكَ

[Phonetic Arabic Reading]

Fa inaha taziduka tola ayyam wa-seni ḥayat wa-salama

La tada‘ a-raḥma wa-al-ḥaq yatrokanika. Taqaladhoma ‘ala ‘onqiqa. Oktobha ‘ala lawḥ qalbika

[English translation]

“For length of days, and long life, and peace, shall be added to you. Let not mercy and truth forsake you: bind them on your neck and write them upon the table of your heart.” (Proverbs, 3:2–3)

The warm wishes for health and prosperity symbolized by Mimouna are best summarized in the traditional blessing, spoken in Moroccan Arabic: trebḥu utse’adu. This translates to “May you be blessed with success and happiness.”

Mimouna is a joyous spring holiday that gathers friends and family around a festive table filled with sweet delicacies and symbolic food. On the Mimouna table you find: a live fish in a bowl which symbolizes fertility and abundance, stuffed dates, zaban (white nougat), candid eggplant, mrouzia (a sweet and spicey meat dish), milk, eggs, wheat, fava beans, and flour

(All recipes can be found in the “Build Your Event” section).

The celebration of Mimouna starts with the Havdalah ceremony “LeMotzei Yom Tov”, which officially ends Pesach, and the prohibition on eating chametz, foods from grain make with leaven.

When guests start arriving to the celebration, hosts often bless each guest using symbolic objects. These symbols differ by community. For example, some sprinkle a few drops of milk on the guests’ heads using lettuce leaves, while others sprinkle flour on guests with their hands. Some offer a date filled with almond-paste. When guest are greeted, the blessing spoken is always the same:

כִּ֤י אֹ֣רֶךְ יָ֭מִים וּשְׁנ֣וֹת חַיִּ֑ים וְ֝שָׁל֗וֹם יוֹסִ֥יפוּ לָֽךְ

חֶ֥סֶד וֶאֱמֶ֗ת אַֽל־יַ֫עַזְבֻ֥ךָ קָשְׁרֵ֥ם עַל־גַּרְגְּרוֹתֶ֑יךָ כָּ֝תְבֵ֗ם עַל־ל֥וּחַ לִבֶּֽךָ

[Phonetic Hebrew Reading]

Ki orech yamim ushenot ḥayyim veshalom yosifu lach. Ḥesed ve-emet al-ya’azvucha kashrem ‘al-gargeroteicha katvem ‘alluaḥ libecha

فَإِنَّهَا تَزِيدُكَ طُولَ أَيَّامٍ، وَسِنِي حَيَاةٍ وَسَلاَمَةً.

لاَ تَدَعِ الرَّحْمَةَ وَالْحَقَّ يَتْرُكَانِكَ. تَقَلَّدْهُمَا عَلَى عُنُقِكَ. اُكْتُبْهُمَا عَلَى لَوْحِ قَلْبِكَ

[Phonetic Arabic Reading]

Fa inaha taziduka tola ayyam wa-seni ḥayat wa-salama

La tada‘ a-raḥma wa-al-ḥaq yatrokanika. Taqaladhoma ‘ala ‘onqiqa. Oktobha ‘ala lawḥ qalbika

[English translation]

“For length of days, and long life, and peace, shall be added to you. Let not mercy and truth forsake you: bind them on your neck and write them upon the table of your heart.” (Proverbs, 3:2–3)

The warm wishes for health and prosperity symbolized by Mimouna are best summarized in the traditional blessing, spoken in Moroccan Arabic: trebḥu utse’adu. This translates to “May you be blessed with success and happiness.”